The phrase “Death by GPS” was coined by park rangers in Death Valley in the late 2000s to describe the mounting cases of visitors getting into trouble by trusting their navigation systems over terrain, signs or local advice. This well-documented phenomenon reflects the tendency to let machine guidance override judgment and perception, a pattern known as automation bias.

I had read many accounts of such events, then nearly repeated one myself. I followed my own GPS into an unfamiliar area and would have ended up in serious difficulty if I had not stopped at a sign telling me not to follow it. The truth is, I had already passed the sign, hit some potholes, remembered the sign, and then reversed back. That moment has stayed with me. Each work starts from a site where someone did what I almost did.

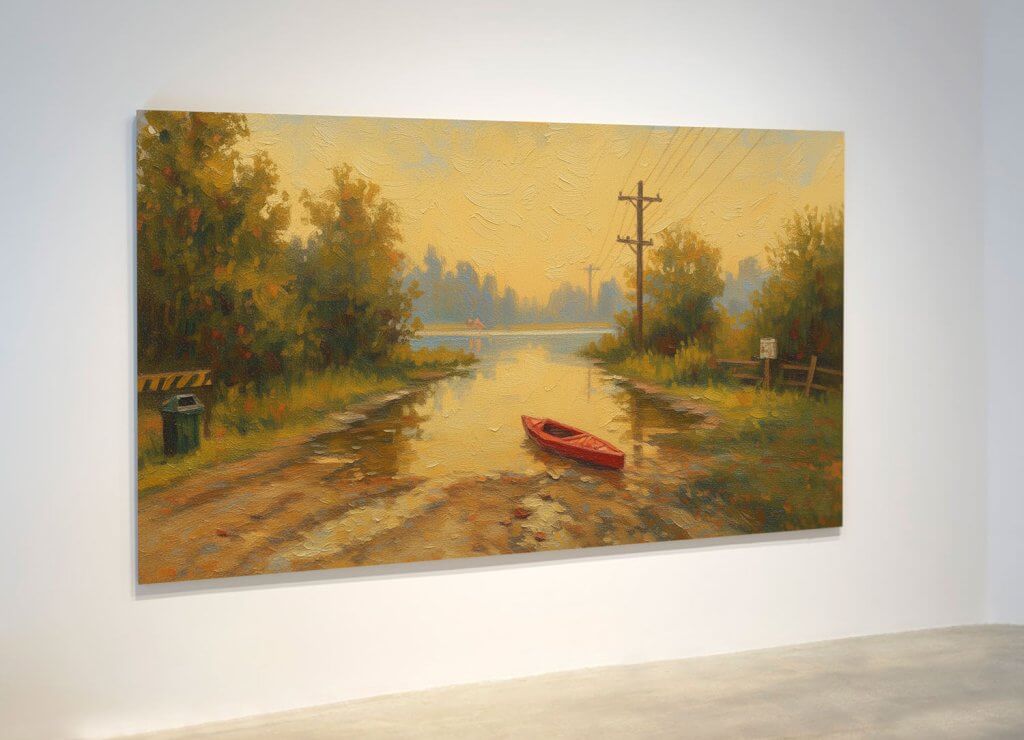

I decided to reach these sites virtually, using the same mapping tools that had once misdirected someone, where I could identify the exact location. From those coordinates I took a screenshot and processed it through a generative diffusion model trained on historical landscape painting. The model acts as a statistical map, charting visual routes in the way a GPS charts physical ones. The output is a pastiche of historical styles applied to raw map data, a meeting of algorithmic abstraction and inherited ways of seeing.

The choice of style matters. Constable’s hedgerows were an elegiac response to enclosure and early industrial change. Colton’s canyon views reflected a preservationist ethos tied to the cultural heritage of the Colorado Plateau. Harding’s ochres, blown by breath, recall a tradition of what he reflects on as “a register of my body, and a register of my reach, my breath and my technique.” These traditions arose from lived engagement with terrain and from social histories of land and memory. Against this, the GPS error shows a logic that ignores rivers, deserts and tides. It replaces local knowledge with a shortest-path calculation that treats the world as a neutral grid.

I remember the sign before the potholes. I rely on GPS to fix coordinates. I use language models to shape research. I turn to diffusion to generate images. Navigation, synthesis and interpretation are outsourced to systems that operate through pattern rather than understanding. There is a cynical appropriation of historical styles, of other people’s labour and of the digital environment dressed up as something other than travelling in borrowed imaginary vehicles. Each stage filters cultural forms through automated tools that impose statistical pattern without context. The mapping platform offers access to the world while enclosing that access within proprietary formats and preselected views. The final image depends upon where a mapping vehicle has been. This now defines the outer limit of my map. I have become death by GPS.

.

Image details:

The Grand Canyon Detour, Landscapes of Death by GPS (after Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton)

35.861°N, 112.249°W (Approximate junction of US-64 and Anita Road), Coconino County, Arizona, USA.

Amber Vanhecke, a student, was following her GPS to the Havasu Falls Trailhead in March 2017. Her navigation system directed her onto an unmaintained, non-existent “shortcut” road across the desolate Arizona desert. After her car ran out of fuel, she was stranded alone for five days, surviving by rationing supplies and leaving a note on her vehicle to guide rescuers. She was eventually rescued by an Arizona services helicopter after she was spotted frantically waving for help.

In the style of Mary-Russell Ferrell Colton, whose landscape paintings of the Grand Canyon region were an elegant, Tonalist response to the unique light and monumental scale of the Colorado Plateau in the early 20th century. Colton saw the region not merely as a subject for painting, but as a cultural space requiring preservation. She co-founded the Museum of Northern Arizona in 1928, to preserve both the anthropological and artistic context of the desert. Her work, like her life’s mission, was an act of enriching human knowledge of the landscape. She used this platform to advocate for the region’s cultural heritage, establishing shows that supported Hopi and Navajo artists and helped preserve their traditional arts and crafts.

The River Plunge, Landscapes of Death by GPS (after John Constable)

52° 36′ 16″ N, 1° 31′ 10″ W River Sense, Sheepy Magna, Leicestershire, England.

A woman in her 20’s was following her GPS when it directed her to turn down a narrow, unlit farm track in March 2011. Ignoring a “ford” warning sign, she drove her Mercedes directly into the flooded river. The car was swept 200 yards downstream, but she managed to escape through a window and swim to the bank.

In the style of John Constable, whose landscape paintings werean elegiac response to the transformation of rural England and the loss of common land, hedgerows and village life under the pressure of enclosure and early industrial change. Sir George Beaumont was a leading early 19th‑century connoisseur and patron whose taste helped shape the British appreciation for landscape painting. He admired Constable’s truthful depiction of the English countryside and supported him both financially and socially: commissioning works, promoting him to other collectors, and hosting him at estates like Coleorton Hall in Leicestershire.

The Leap, Landscapes of Death by GPS (after Dale Harding)

-27.42168°S, 153.11183°E (Approximate coastline near Manly, Brisbane, Australia), Moreton Bay, Queensland, Australia.

In March 2012, three Japanese tourists visiting the Gold Coast were attempting to drive to North Stradbroke Island, Australia. Following their GPS directions, they turned their rental car off a road and drove directly onto a tidal ramp. The GPS failed to account for the 15 kilometers of ocean and mudflats separating the island from the mainland. Their vehicle quickly became stranded in the mud as the tide came in, requiring a rescue by police and local residents.

In the style of Dale Harding, whose large painting, The Leap/Watershed, links contemporary abstraction, performance, and endurance to 20,000 years of Indigenous art from central Queensland. Harding’s decision to use his own breath to blow red and light ochres onto the canvas – a technique used in the rock art galleries of Carnarvon Gorge – was an exhausting act of physical duration, leaving the artist spent and unable to complete the desired block of color. This raw physical effort is a profound meditation on the lived connection to Country, history, and geography (including the tragic history of The Leap massacre). The tourists’ GPS error, in contrast, represents the ultimate de-contextualisation of geography – replacing a 20,000-year history of local, life-saving knowledge with a simple, digital shortest-path algorithm that dismisses 15 kilometers of life-threatening water, failing to breathe any life or truth into the actual landscape.

The Slough, Landscapes of Death by GPS (after Anna L. Fonda)

47.5878∘N,122.1834∘W Mercer Slough Nature Park, Bellevue, Washington, USA

Three Mexican tourists followed GPS down a boat ramp and into a creek/slough in the fog. They swam to shore.

In the style of Anna L. Fonda, who settled in the Tacoma/Seattle area around 1892, which is just across Puget Sound and Lake Washington from Bellevue. She is considered an important early painter of the region. According to Gemini Flash LLM “One of her known works, dating to around 1900, is an oil painting that depicts an Indigenous person paddling a canoe on Lake Union (which is directly connected to Lake Washington, near Bellevue). This perfectly captures the local water-based activity in a historical painting style.”